UNFATHOMABLE LOSS

Steve Bonano, a deputy chief with the NYPD, died after a two year battle with a 9/11 cancer

Steve Bonano, who rose up through the ranks of the NYPD to become a Deputy Chief, and was in charge of the Department’s elite Emergency Services Unit during the months after 9/11, died January 17, 2105 after a two year battle with a rare, lethal cancer. His doctors say the illness was a direct result of the work he did at Ground Zero during the weeks and months after the attacks of September 11, 2001. He was 53 years old.

I think continually of those who were truly great. …

The names of those who in their lives fought for life

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s center.

Born of the sun they traveled a short while towards the sun,

And left the vivid air signed with their honor.

—Stephen Spender

In 2009 Steve took a leave from the NYPD to pursue a Master’s Degree in Public Administration at Harvard University’s Kennedy School. When he was unable to attend a class reunion his fellow students made this video for him.

Steve Bonano’s career is filled with so many accomplishments that it is a bit of a surprise when he talks about what he still feels is the most memorable moment in his career.

Steve Bonano’s career is filled with so many accomplishments that it is a bit of a surprise when he talks about what he still feels is the most memorable moment in his career.

“A call came in for shots fired with the possibility of multiple victims,” Steve remembered. He had just turned twenty-one and had only been on the job for a year.

“You could tell this was going to be a bad one,” he said. “As we drove to the location, you could see a caravan of red police lights. Every one of the officers was rushing toward the unknown. While they raced toward danger, not one of them was thinking about the risk to themselves or the possibility of a bad outcome. Looking at all those police cars and those brave cops, I began to understand that law enforcement is not a job, it’s a calling. It’s a profession where we take an oath to protect the innocent and apprehend those who hurt them. It made me so proud to be a police officer. That was my first year on the job. Thirty years later I still feel the same way.”

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

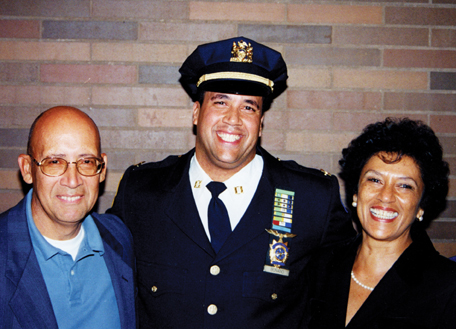

| Steve and his parents Vivian and Tony, on the day Steve was promoted to captain in October 1998. “I could not have had more supportive parents,” Steve said. “Without their help it would have been hard for me to get my commercial pilot’s license, a requirement to become a pilot with the New York City Police Department.” | Steve with his fiance Miriam Rivera this past summer on Block Island. They planned to marry later this month. "Steve was the love of my life," Miriam said. "Heaven called for him too quickly but I know one day we will meet again and as we planned, we will say our "I do's" and continue on with our wonderful, love-filled journey." |

It wasn’t long before Officer Bonano’s bosses began to notice that he was unusually observant and especially good at figuring out who had an illegal firearm. “I grew up in a bad neighborhood,” Steve said. “I wasn’t a bad kid, but there were a lot of kids who were, and I knew how they acted. If you’re doing something illegal, you don’t feel comfortable around cops. Once I became a police officer, I picked up immediately if someone was nervous when I was around.”

It wasn’t long before Officer Bonano’s bosses began to notice that he was unusually observant and especially good at figuring out who had an illegal firearm. “I grew up in a bad neighborhood,” Steve said. “I wasn’t a bad kid, but there were a lot of kids who were, and I knew how they acted. If you’re doing something illegal, you don’t feel comfortable around cops. Once I became a police officer, I picked up immediately if someone was nervous when I was around.”

One night Steve was working with Dave Erosa, his best friend since kindergarten at the Holy Cross Grammar School in the Bronx. It was a Wednesday evening, and they were working the four to midnight shift in the 46th Precinct.

They had just gone out on patrol when they saw a car ahead of them go through a stop sign. The officers pulled the vehicle over and kept their hands over their holsters as they approached. “I went to talk to the driver in the front seat, and Dave opened the back door of the car on the passenger’s side,” Steve remembered. “Within seconds, Dave and the guy in the back seat were fighting. Dave yelled, ‘He has a gun.’” A simple stop for not heeding a stop sign had escalated.

“I grabbed the driver in the front seat by the collar and pulled him out of the car, all the while keeping my weapon aimed at the passenger. I called for backup. I knew they could tell by my voice we were in trouble. All I had to say was, ‘6-Adam, 182 and Creston,’ and help was on its way. I barely got the words out of my mouth before I heard the sirens. When you’re in trouble, there is no greater sound than that one. The cavalry was on its way.”

“You couldn’t have a better experience than working with Steve,” Dave said. “He’s a great leader and really good at getting guns off the street. He is a great cop with a big heart.”

|

|---|

| A lot of people would be surprised that Steve, a tough street cop, was a passionate lover of animals. Along with his fiance Miriam, he was totally devoted to his three Bichon Frises. He’s pictured here with Snowball who many people said are the three most spoiled dogs on the planet. |

One night when Steve was on patrol with Tommy Crowe, they heard a barrage of gunfire. They headed in the direction of the shots. Tommy was driving. He made a left turn, and both officers saw a man standing on the corner, randomly shooting a firearm.

“Another cruiser pulled up at the same time, and we almost ran into each other,” Steve said. “Once we got closer, we could see the man was shot up pretty bad, but he still had a gun in his hand.”

The cops pulled their weapons and ordered him to drop the gun. The suspect was incoherent. The police could tell he could not hear them. One of the officers, Joe Zallo, tackled the man and got him face down on the street. Steve said despite the fact he was riddled with bullets, but the man put up a fight to keep hold of his gun. “A few seconds passed before Joe was able to get hold of the weapon and put the cuffs on,” Steve recalled. “When Joe stood up, he was covered with blood.”

When someone who’s had little or no contact with criminals witnesses a police officer acting aggressively toward someone on the street, they often get the impression that cops are violent people who enjoy preying on victims. But the reality is just the opposite. Bystanders at the scene, unaware the man was armed, must have wondered why it was necessary for a police officer to tackle someone who was so badly wounded.

As Steve was reporting the incident over his radio, several people ran up and pointed to a Jeep that was stuck in traffic. “The people in that Jeep shot this guy,” they said, pointing to the man who was still lying in the street in a rapidly growing pool of blood. If they were right, Steve knew the people inside the Jeep would be heavily armed.

Zallo and his partner stayed with the handcuffed suspect while Tommy and Steve ran toward the Jeep. Three men were inside. The cops ordered them out of the car and told them to keep their hands high in the air. When they searched the vehicle, they found two machine guns, an AR-15, and a semiautomatic handgun. These were heavily armed criminal suspects even by New York City standards. They were only two-and-a-half hours into their shift, and they had four suspects, two machine guns, and a semiautomatic.

Tommy Crowe has known Steve Bonano for more than twenty years. The two men were partners for much of that time. “If I had to describe Steve,” Crowe says, “ I would say the quality that impresses everyone the most is his intelligence. He’s extremely smart and can quickly size up a situation.”

“One time a cop in a neighboring precinct was shot,” Tommy said. “They rushed him to the hospital, and Steve and I were the first people there. Most people would be surprised at the chaos that goes on at a hospital when the doctors are operating on a high-profile shooting victim. Reporters and photographers are everywhere. They’ll barge right into the operating room if they can in order to get their story. When Inspector Louis Anemone showed up and saw Steve, he asked him to take control of the scene.

“When Steve was put in charge, a reporter tried to push his way past him to get into the ER,” Tommy continued. “Steve stood there with his arms folded, blocking the reporter’s way. He told the reporter he didn’t care what credentials he had. There was a police officer in there, and most likely he was dying. There was no way a reporter was going to get by him. When he has to be, Steve is very intimidating.”

In the late 1980s active cops in the Bronx were averaging several arrests each year for possessing illegal firearms. Known in the NYPD as “gun collars,” Steve Bonano was making several every month. People started to call him the Gun Man.

In the late 1980s active cops in the Bronx were averaging several arrests each year for possessing illegal firearms. Known in the NYPD as “gun collars,” Steve Bonano was making several every month. People started to call him the Gun Man.

One night Steve was working with Jimmy Gildae, a newly promoted sergeant who had just been assigned to the precinct. Like Steve, Jimmy had been very active in the 4-6, and the men shared a strong work ethic. Steve said Jimmy was a cop who was first on the scene and first through the door. “He was the guy you could count on to watch your back,” he said.

It was the start of their shift. Steve and Jimmy were sitting in the car, sipping coffees, and watching the street when they heard shots. Seconds later a limousine with shaded windows drove by. “We knew right away there was something wrong with that limo,” Steve said.

They turned on the lights and pulled the limousine over. Contrary to what most people believe, when the cops approach a vehicle, they do not unholster their firearms. “We approach cautiously with our hands on the grips in case we need to pull our weapons,” Steve explained. “In most situations like this, you never pull your firearm. There’s always the chance you’ll end up wrestling with the suspect, and that can be bad if you have your gun out of its holster.”

This time they were lucky. The suspects, young kids in their early twenties, followed orders. They got out of the car with their hands in the air. Once they were cuffed, Steve watched the suspects while Jimmy used his flashlight to search the vehicle. That’s when they found the guns—an Uzi machine gun, a Tech-9, and a semiautomatic.

When people outside of law enforcement ask cops like Steve and Jimmy how they have the courage to run toward a car whose occupants are heavily armed or shooting, they shrug. “I am not sure,” Steve says. “Maybe you don’t get scared because it’s all happening so fast. And thank God most people are good people and will not shoot a cop. I’ve always believed that I am not going to get shot.”

The Quota Sergeant? No way!

The dictionary defines a “glass ceiling” as an unacknowledged discriminatory barrier that prevents minorities and women from rising to positions of power. While Steve readily acknowledges there has never been a door yet that shut on him because he’s Hispanic, he has not been immune from wisecracks about his ethnic background.

“To some guys, I know I’ll always be the ‘quota sergeant’ even though affirmative action had nothing to do with my promotions. It doesn’t matter how well I do. A few people will always believe I moved ahead because the NYPD was being forced to promote minorities. During the 1980s an anti-discrimination lawsuit forced the Department to hire a percentage of minorities for every non-minority who was promoted. If you were black or Hispanic or a woman and you took a promotional exam, you had an advantage over a white male candidate. As a result of the lawsuit, minorities who got promotions were stigmatized. It caused problems for people like me who passed the exam and got promoted without the benefit of a quota system. I remember this one guy who kept getting in my face after I was promoted to lieutenant. He’d say, ‘I know you, you’re the quota sergeant.’ It didn’t matter to him that I had gotten one of the highest marks on the lieutenant’s exam and had made over three hundred arrests before I even made sergeant. I knew that no matter what I did, to him I’d always be the quota guy. When I became a police officer, I was naive about how some white guys would feel about me, but I don’t worry about it any more. I’ve learned to accept that there’s a small group who will always think I got where I did because I’m a minority.”

If there is a glass ceiling in the NYPD, Bonano rocketed right up through it. He scored high on the sergeant’s and lieutenant’s tests. Several years later he decided to take on the captain’s exam, a test considered by many as being more difficult than the New York State bar exam. Steve took six weeks off to study, and he worked at it twelve hours every day. When the marks got posted, he was crushed: He’d barely passed. Even after taking a one-year leave to earn a master’s degree at Harvard University in 2009, he still says the captain’s exam was the most challenging test he ever took.

The doors kept opening for Steve, and he kept marching through them. He became the first Hispanic officer in the history of the NYPD to command one of the agency’s most elite divisions, the Emergency Service Unit. “Ever since I joined the Department, I always felt I was the poster child for all the possibilities available to anyone who joins the New York City Police Department.”

Drugs, guns and prostitutes

After two years in the 4-2 Precinct, followed by another two in the 4-6, Steve went to the Vice Unit in 1986. Working as an undercover investigator, he spent almost four years investigating prostitutes, people running illegal gambling operations, and employees of social clubs, after-hours bars with no operating licenses and a lot of crime. Steve is still amazed that his friends outside law enforcement were envious about the fun they imagined he was having on the prostitution detail.

“People have no idea what these women were like,” he said. “Every arrest requires the arresting officer to inventory and voucher the contents of their purses. You can’t imagine how disgusting it was to have to do that. They had bottles of creams and lotions for sexually transmitted diseases. Everything was filthy, and it smelled really bad. I’d tell my friends, there’s no way anyone would want to have sex with these women. You didn’t even want to touch them.”

While dealing with the prostitutes was unpleasant, shutting down social clubs was dangerous. “These places are really bad,” Steve said. “They sell liquor without a license, which on the face of it doesn’t sound dangerous, but there are usually a lot of drugs and guns being bought and sold, and they attract a serious criminal element. It’s extremely dangerous for the undercover cops to go in and get enough evidence to make the arrests and shut the places down.”

Once Steve was sent into a club in a particularly bad section of the Bronx. He had a small gun hidden in his crotch. “If they didn’t know you, you’d get searched before they let you in,” he said. “I had been searched hundreds of times before, and no one had ever discovered the gun. I never thought they’d find it, but they did.”

The bouncers quickly surrounded him. Steve knew he had to talk fast. “I told them, ‘Look, this neighborhood is rough, and I have a gun to protect myself.’ I figured they would beat me or maybe something worse, but they decided to just physically throw me out.”

Back on the street, his relief soon gave way to frustration. The way Steve saw it, he had a job to do, and he had been interrupted. He returned to his lieutenant at a predetermined location and told him what happened. Steve gave the lieutenant his gun and told him he was going back inside. The lieutenant looked stunned as Steve walked back toward the club.

When he got to the front door, Steve told the bouncer he’d gotten rid of his gun. “I told the guy I didn’t want any trouble. I just wanted to have a drink and hang out.”

They let him in. After sitting at the bar for two hours posing as a regular patron, Bonano established a rapport. From that night on, he was able to come and go when he pleased. Eventually he witnessed enough criminal activity to get a search warrant. When Vice detectives and uniformed cops from the precinct raided the club, Bonano was handcuffed and removed from the scene along with the other patrons and employees. The arresting officers read them their rights and put them under arrest, and the club was closed.

|

|---|

| Steve and Brigadier General Chuck Yaeger. Yaeger was the first pilot to fly faster than the speed of sound. |

From Vice, Steve Bonano was transferred to the 52nd Precinct. From there it was on to the Aviation Unit. Not many people knew he had been flying since his dad took him up in an airplane for a surprise ride on his tenth birthday. He’d had a passion for it ever since. Soon after he was promoted to sergeant, a memo went out that the Department was looking for pilots. Steve decided to do everything he could to become a pilot for the New York City Police Department.

As he began to talk to people about getting a transfer, he got some negative feedback. “I was surprised that some people were not impressed with Aviation,” he said. “I knew that helicopters are great at certain kinds of patrol. They’ve got infrared equipment and can light up a really large area. If officers on the ground are chasing someone on foot and lose their suspect, the helicopter can light up the neighborhood, pinpoint a criminal suspect, and pass his location on to the cops.”

Not everyone saw it that way. When Steve approached one inspector about transferring to the unit, his reaction was hostile. “He told me that in his opinion, a helicopter is like a flying radio car that can’t make stops. In his view, for law enforcement, aircraft are pretty much worthless. He seemed to think the Aviation Unit was just a bunch of good old boys up in the air screwing around. He told me I belonged on the street, that if I went to Aviation, I would be wasting my training and my talents.”

In New York City, where most of the cityscape is dense and decidedly vertical, helicopters don’t play as significant a role as they do, say, in Southern California, with its endless freeways and one- and two-story structures spread over a vast area. Air support units in the Big Apple can’t follow fleeing suspects like they can in other areas because of the tall buildings and narrow streets.

Still, Steve believed helicopters were effective tools in the law enforcement arsenal, and he was determined to achieve his goal. To apply, he found out that he needed a commercial pilot’s license, which required a major investment of time and money. When the flight school told him the cost for the training, he almost gave up. There was no way he had that amount of cash. But when Steve’s father learned his son had put his plans on hold, he made the decision to help him out.

Four years into his eight-year stint with Aviation, Steve Bonano made history. He and his copilot, Matt Rowley, had been up for over an hour when the dispatcher’s voice came blaring. A highway unit had attempted to stop a stolen vehicle, and a chase ensued.

“Matt and I picked up the chase,” Steve said. “We followed the cars with the helicopter. The vehicles finally came to a stop in a shopping center. The next thing we knew, the officer was fighting with the driver. The suspect managed to break free and run toward the supermarket. The officer took off after him. I think that’s when the adrenaline kicked in, and we made the decision to land.”

As they brought the helicopter down in the shopping center parking lot, they could see they had a problem. An elderly woman sitting in her car was right in the middle of the only space big enough for them to land. The officers signaled her to move. “She was staring at the chopper,” Steve remembered. “She looked frozen with fear. Finally she got her car going and drove it out of the way.”

Steve jumped out, and Matt stayed with the bird. “When I got into the store, I saw the officer chasing the guy through the aisles,” he said. “They were coming right toward me.” Steve ran toward the suspect and tackled him. He pulled the suspect’s arms behind his back, forced his wrists together, and got the handcuffs on. It was only at that moment that it hit him that landing the helicopter might have been a very bad idea.

After making sure the officer who began the chase was okay, Steve raced back to the chopper, desperately trying to tuck his shirt back into his trousers as he ran. He was completely out of breath when he got back to the helicopter. Matt was ready to go, and they lifted off.

They were feeling pretty good. The cop was okay, and they had nabbed a bad guy. They took a moment to enjoy the calm before the storm. The moment turned out to be a short one. Just a few seconds after they lifted off, a call came in on the radio.

“I can still hear it now,” Steve said. “‘Base to number six.’ Matt and I looked at each other. It was the Commanding Officer of the Aviation Unit. I knew the same thing was going through Matt’s mind. He’s never on the radio, and we know why he’s calling.”

“Did you just land a helicopter in a shopping center and engage in a foot pursuit?”

Steve thought for a quick minute about lying but decided that would probably be his second bad idea that day. It was clear the boss knew something. “That’s affirmative, Sir.”

“I’ve got the Mayor’s office on the phone,” the commander bellowed into the radio. “They called to tell me someone from Aviation landed a Department helicopter in a shopping center parking lot.”

The Commander told them to land the chopper and call him immediately from a landline. He wanted the conversation out of earshot of the police scanners. Matt and Steve knew that whatever the boss had to say, he wasn’t interested in having anyone hear it.

Matt, who would be facing the wrath of the boss as well, had an idea. “No sense both of us getting transferred,’ he joked. “Why don’t you say you ordered me to do it? Tell them all I was doing was following your orders.”

In the end, Steve and Matt never faced disciplinary action, and the people who had doubted that Aviation had a legitimate role in law enforcement were impressed. Chief Anemone, now the Chief of Patrol, said, “That’s what they should be doing up there—apprehending criminals.”

The commanders who disparaged Steve’s ambition to go to the Aviation Unit realized it didn’t matter where a guy like Steve works or on what assignment. He’s a street cop, whether he’s flying a helicopter or walking a beat. If he sees an officer in need of assistance, that’s it.

The guys who made Steve want to be a cop

For Steve Bonano, pursuing a career in law enforcement was a long shot. No one in his family had been a cop, and he had never had much personal exposure to the police. But when he turned fifteen and got a summer job as a lifeguard at a public pool in the Bronx, an older cop, Al Vazquez, took an interest in Steve. Vazquez and another officer, Harry Gonzalez, were both assigned to the pool for the summer. They enjoyed telling the young lifeguard stories about their adventures working as cops. They encouraged him to think about joining the force.

|

|---|

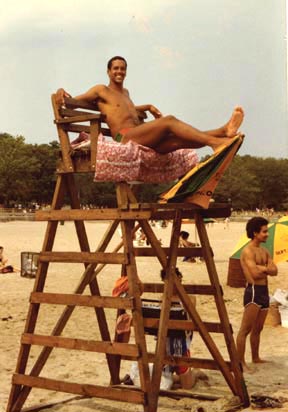

| When Steve was 15 years old he worked as a lifeguard at Orchard Beach in the Bronx. The following summer Steve met two NYPD veteran cops – Al Vazquez and Harry Gonzalez who patrolled a pool he worked at. They enjoyed telling Steve about their adventures working for the New York City Police Department and encouraged him to join the force. |

“One experience I had at the pool made a big impression,” Steve said. “It was hot and sunny, and the pool was filled with young kids and lots of teenagers. It was around one in the afternoon when I heard a strange noise. It was like a rattling, rumbling sound. All of a sudden I see this huge number of guys, bigger and older than me, climbing over the fence that surrounded the pool. It seemed like there were hundreds of them. I knew by the colors of their clothing that they were all in the same gang, the Savage Skulls. We had a lot of gangs in the Bronx in those days, and the Savage Skulls was one of the worst. Within seconds, they circled the pool. They started chanting at the swimmers. I was the only lifeguard on duty, I was fifteen years old, and I was scared. I was afraid to turn my back on them, so I backed up slowly toward the pool house. I was praying they wouldn’t notice me. I found Officer Vazquez in the locker room. I told him the Savage Skulls had circled the pool and I was worried what they were going to do to the kids. I’ll never forget what happened then. Vazquez jumped out of his chair and pulled his gun belt off of a hook on the wall. I remember his face turned beet red. He looked furious. He growled, ‘What in the hell are they doing here?’ On his way out to the pool, he called it in on his radio. Vazquez knew that with one cop against dozens of gang members, he might need help.”

When the officer got out to the pool, he looked around and sized up the scene. He yelled out, “Which one of you is the leader? Step forward.”

“I thought you could probably hear his voice from miles away. He was clutching his nightstick, holding it low on one side. When one of the gang members stepped forward and announced he was the leader, Vazquez grabbed his arm and did some kind of jujitsu move. The next thing I see is the so-called leader down on the ground and scared to death, just like that. By the time Officer Vazquez got him in cuffs, everyone else had scattered. I looked around. I couldn’t believe they were all gone. We found out later that there were probably forty of them, not the hundreds I’d thought at the beginning. Yet that one cop took on all those tough guys by himself. A couple of minutes after he called it in, the first police car showed up. By then Vazquez had everything under control. The gang was gone, and the kids went back to swimming. To me he seemed like Superman. I decided right then that when I grew up, I wanted to be just like him. Al Vazquez and Harry Gonzalez made me want to be a police officer.”

Over his three decades with the NYPD, everywhere Steve was assigned, morale went up. Within months, most cops under his command found they had new enthusiasm for the job. They took on more work and did it with pride. He was especially good at advising rookies about the crucial sets of skills they had to master before they would be effective street cops. “I tell them, ‘You’ve got to be nosy, you’ve got to engage people, and you’ve got to shake things up if you want to find something. Go out and ask them what they’re doing. Find out if there’s anything going on. Don’t be shy.’ Nine times out of ten, it’s nothing. When there is something, I tell them that’s when they have to be ready for things to escalate. I warn them over and over. Be ready for the unexpected. When it happens, you will have only a second to react.”

Steve knows that enforcing the laws and protecting innocent people from harm is hard work. A lot of police officers burn out. “I never stop trying to motivate the burned-out cops whose views have become negative,” he says, “but I like to give more attention to the ones who are still into the job. I like to focus on those who, with a little encouragement, will get out there and try their best to be great law enforcement officers despite the enormous frustrations of the job.

People who go into law enforcement must work hard to overcome burnout. The signs are unmistakable. Everyone and everything becomes aggravating. Negativity and cynicism seem to overwhelm everything. The tendency to isolate oneself from friends and neighbors who are not in law enforcement accelerates. With burnout, the jokes that have always been the police officer’s best defense mechanism against the constant exposure to rage, violence, and man’s inhumanity to man don’t seem funny anymore. In Steve’s case, after close to three decades on the job, he is relieved that his sense of humor is still intact.

Humor is a double-edged sword for law enforcement. The sick jokes, pranks, and endless hazing that go on between cops are their best defense against the brutal world they are thrust into. It is part of life in every police station in the United States. Law enforcement officers try to keep laughing so they can tolerate the horror they witness, from abused children to car wrecks and all manner of violence and death.

|

|---|

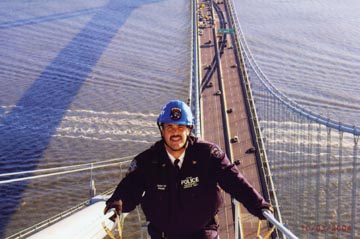

| Inspector Steve Bonano on top of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, 2004. When this photo was taken, Steve was commander of the NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit. |

But what most police officers find hilarious, civilians find strange. While their jokes help officers stay sane, they are also a wedge between cops and the rest of the world, which has trouble understanding how normal people can joke about events that are tragic.

While Steve may be able to able to joke about sad things he sees on the street, he admits that the constant exposure to rapists, muggers, drug dealers, prostitutes, thieves, and all the other unsavory people police deal with daily can change one’s own view of human beings. “A lot of these people you encounter are really horrible,” he says. “If you let it get to you, you can lose your faith in the human race.”

And now Steve Bonano – this remarkable man who did so much good work for his Department and the people of the City of New York – has gone to a better place. But rest assured, his profound impact on everyone who had the fortune of working with him or knowing him, will continue on forever.

You can read more about Steve in the book: Brave Hearts: Extraordinary Stories of Pride, Pain and Courage.

Read more about Steve Bonano - directly from the pages of Brave Hearts: Extraordinary Stories of Pride, Pain and Courage.